In my last 2013 vintage blog post, I expressed skepticism about the “free ride” Mother Nature had provided this year with the early, but perfect, budbreak, flowering and fruit set. As it turns out, foolish were those who danced in the sun in celebration, wise were they who called the bluff. The 2013 growing season has been anything but a free ride since June.

On June 23, brooding, nimbus clouds casted a shadow over the North Bay and dropped a little over a half-inch of rain across Sonoma and Napa. While this unseasonal precipitation volume barely dented the annual rainfall average, the days-on-end of high temperatures and 100 percent humidity that followed into the upper half of July increased the chance for mildew pressure in the vineyards. Fortunately, we were prepared. Our winemaker’s 38 years of experience is invaluable in situations like these.

For viticulturists who thoughtfully positioned their grapevine shoots, properly thinned and balanced the high-yielding crop, and leafed the morning side of the vine rows to aid sun exposure and air movement, losses in both quantity and quality were minimized. The long hours that Ranch Manager Brent Young and our family growers have invested in preserving this year’s perfect fruit set are paying off in the uniformity of véraison amongst the clusters, all of which are hoping to earn their way into a bottle of Jordan Cabernet Sauvignon.

Beginning mid-July this year, depending on grape variety and vineyard elevation, the sugars produced through photosynthesis made a drastic route switch within the vine. Up to this point, because of its climbing habit, the vine has been investing its sugar energy source into shoot development, with the simple mission of out-competing the neighboring vine for the sun’s rays. Now that the vine has established enough big, floppy leaves to produce a level of photosynthate adequate to fully ripen its clusters, it is rerouting the sugar energy source from its shoot tips to the grapes. In addition to the visual pigment change, the berry will begin to soften and further expand as the sugars accumulate. The high level of acids in the berry produced back during the first stage of development will begin to drop in concentration, and the pH of the grape juice will increase. Basically, véraison signals sugars to rise and acids to decline.

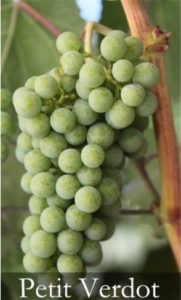

During the first two stages of development, the green berries, such as the Petit Verdot (pictured), contain enough chlorophyll to supply their own photosynthate for energy, while most of that captured by the leaves is rationed to the growing shoots. At véraison, the grapes make a switch to using the malic acid accumulated during the first stage instead of sugar as their energy source. Simply put, the attractiveness of each berry and the chance of the seeds within it being dispersed is largely dependent on its sugar level; hence, it would be counterproductive and ultimately detrimental for the survival of the species if the grape was to deplete its sugar through respiration.

During the first two stages of development, the green berries, such as the Petit Verdot (pictured), contain enough chlorophyll to supply their own photosynthate for energy, while most of that captured by the leaves is rationed to the growing shoots. At véraison, the grapes make a switch to using the malic acid accumulated during the first stage instead of sugar as their energy source. Simply put, the attractiveness of each berry and the chance of the seeds within it being dispersed is largely dependent on its sugar level; hence, it would be counterproductive and ultimately detrimental for the survival of the species if the grape was to deplete its sugar through respiration.

The goal of the winegrower is uniform maturation of all the berries on a cluster, of all the clusters on each vine and of every vine within each vineyard block. Due to the color change at véraison amongst the berries of red variety vines, this conversion provides the best opportunity for the viticultural teams to pass through the vines and remove any clusters or portions of that are lagging behind. This “thinning” of the fruit better focuses the vine’s energy into ripening the remaining grapes on the vine in the desired uniform manner. Our estate crew and growers have been véraison thinning all week, as documented in our Twitter feed. We expect harvest to begin with our Russian River Chardonnay in about 3-4 weeks, which is about 8-10 days earlier than usual. Our Merlot grapes, the earliest ripening of the Bordeaux varieties, could arrive at the crushpad around the same time.

The goal of the winegrower is uniform maturation of all the berries on a cluster, of all the clusters on each vine and of every vine within each vineyard block. Due to the color change at véraison amongst the berries of red variety vines, this conversion provides the best opportunity for the viticultural teams to pass through the vines and remove any clusters or portions of that are lagging behind. This “thinning” of the fruit better focuses the vine’s energy into ripening the remaining grapes on the vine in the desired uniform manner. Our estate crew and growers have been véraison thinning all week, as documented in our Twitter feed. We expect harvest to begin with our Russian River Chardonnay in about 3-4 weeks, which is about 8-10 days earlier than usual. Our Merlot grapes, the earliest ripening of the Bordeaux varieties, could arrive at the crushpad around the same time.

With the grapes now purple on the vine, those visiting wine country during this time naturally gravitate towards the vineyards for a sampling, or sneak preview of the vintage, only to find themselves puckering in disgust. The reason for their gustatory expectations falling short is simple: The seed is not yet ready to be spread. The biology of it all is genius. That visitor’s hesitance to snatch another berry is evidence that the system works. As the seed matures, the berry will become increasingly attractive for pilfering by critters, including wine country visitors and winemakers. So in response to the rumor that wine grapes don’t actually taste good, well, just ask those who visit in late September and early October.